Reframing basic needs to encourage students to share

This is the first pilot in our series of tests to increase student success through basic needs support.

We know that meeting students’ basic needs—like food, housing, and healthcare—is essential for learning and persistence. But too often, students’ needs go unspoken or unnoticed—making it harder to connect them with resources like CalFresh, housing assistance, or mental health care, even when they’re eligible. In this pilot, we tested a simple but powerful idea: What if we could ask about basic needs in a way that meets students where they are—and helps them recognize the support they deserve?

Our approach

Students frequently under-report their basic needs insecurity, which limits the institution’s ability to connect them with critical support. We hypothesized that reframing these questions would make it easier for students to recognize and report their challenges— giving us a more accurate picture of who needs help, and when.

We tested two versions during student onboarding, both grounded in behavioral science and basic needs research:

Presumptive Framing positioned support as something many students use, and invited them to select which types of resources might help—rather than asking if they needed help. This aimed to reduce stigma and normalize support-seeking.

Concretization used four short, specific questions about recent experiences, like struggling to pay rent or afford food. This aimed to reduce ambiguity and help students recall actual moments of need.

Both designs aimed to make it easier for students to recognize and share their experiences—something we heard directly from students was a key challenge, especially for those unsure whether their situation “counted” as needing help.

The results

Students who received either new question framing were 2.5x more likely to report a basic needs challenge, and 2.2x more likely to answer the question at all—giving Calbright a much clearer view of who might need support.

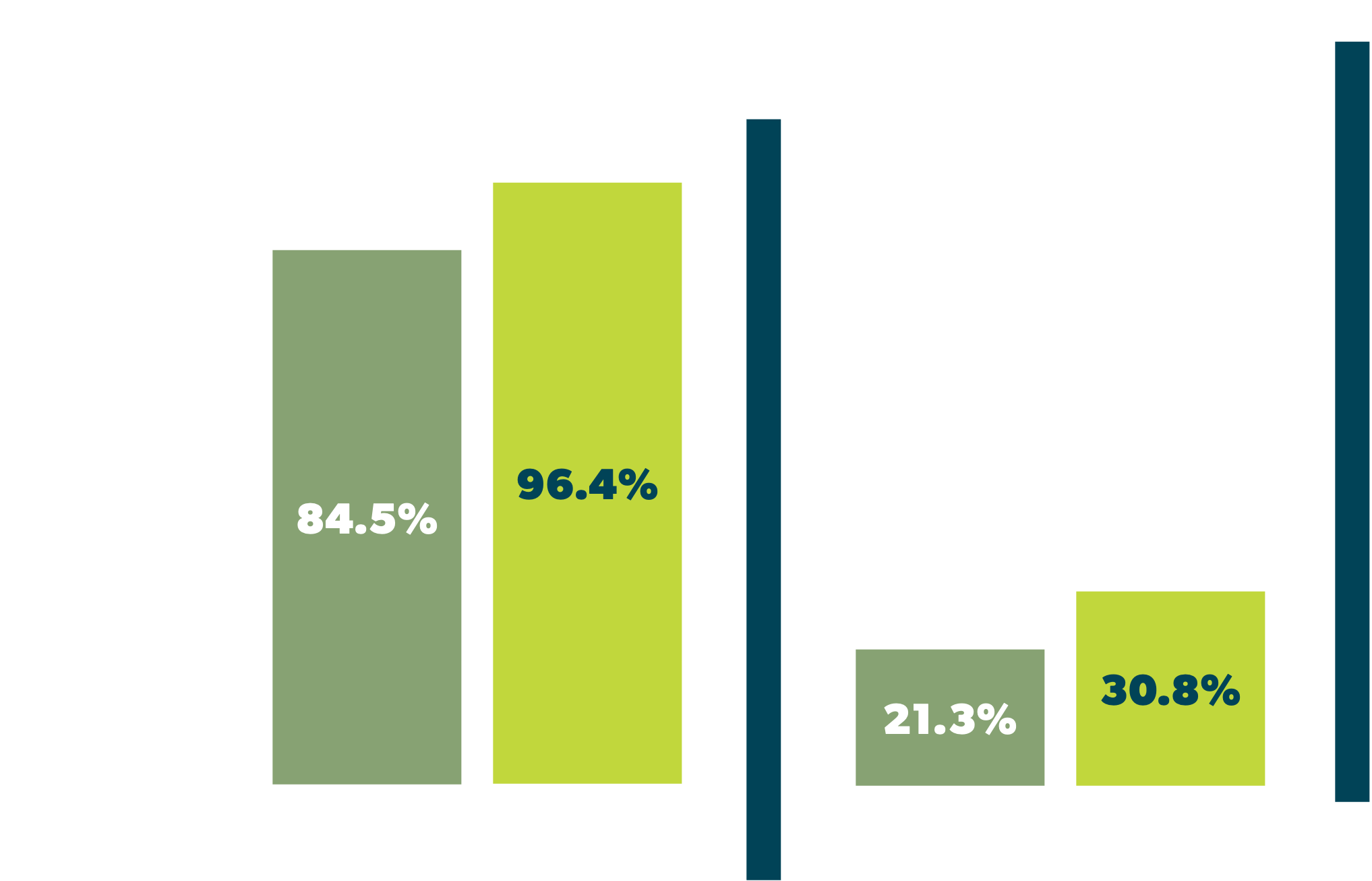

To understand which framing worked better, we compared them directly. Both improved reporting, but Concretization outperformed Presumptive Framing:

Students were 1.5x more likely to report food or housing insecurity compared to the Presumptive version.

They were also more likely to respond—96% response rate vs. 84%.

This test suggests that how we ask matters. Clearer, more supportive language helped more students open up—which helps Calbright reach them with the right support, sooner.

This approach is also highly adaptable. It can be used in onboarding forms, short surveys, or live conversations—and works across different programs and populations. With just a few thoughtful changes to how we phrase questions, we can better support students in meeting their most essential needs.